|

Strabismus, Crossed, Wandering Eyes Correction

|

|

04-07-2014, 01:39 PM

(This post was last modified: 07-12-2016 02:37 PM by ClarkNight.)

Post: #1

|

|||

|

|||

|

Strabismus, Crossed, Wandering Eyes Correction

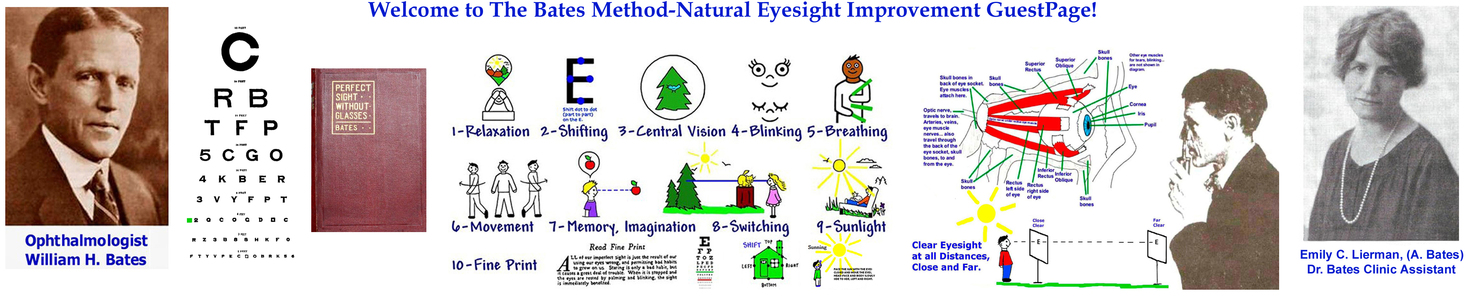

Dr. Bates and modern teachers state that Strabismus is most always caused by outer eye muscle tension, tension, strain in the mind-brain, emotions and imbalanced brain hemisphere function. http://cleareyesight-batesmethod.info/id66.html Switching practice also improves the vision at all distances, close, middle and far; http://cleareyesight-batesmethod.info/id9.html http://cleareyesight-batesmethod.info/id8.html Below; after neck, spine injury caused by a bad Chiropractor' the eyes have astigmatism, double vision, bouts of a strange type of white 'like static on a old time tv screen' blindness when awaking at night with a stiff neck, head, shaking eyes, vertigo and a wandering eye; Later much improvement in eye movement, vision after Physical Therapy... and Natural Eyesight Improvement; Present videos show complete eye-vision improvement; https://www.youtube.com/user/ClarkClydeN...rid&view=0 Still some tension at times when injury acts up but for brief time. Many treatments in Dr. Bates book and Better Eyesight Magazine; http://www.cleareyesight.info/naturalvis.../id28.html Squint Number BETTER EYESIGHT A MONTHLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE PREVENTION AND CURE OF IMPERFECT SIGHT WITHOUT GLASSES November, 1920 MAKE YOUR SQUINT WORSE This will help you to cure it Crossed, Wandering Eyes, Strabismus Cures There is no better way of curing squint than by making it worse, or by producing other kinds of squint. This can be done as follows: + To produce convergent squint, strain to see a point about three inches from the eyes, such as the end of the nose. To produce divergent squint, fix a point at the distance to one side of any object, and strain to see it as well as when directly regarded. + To produce a vertical squint, look at a point below an object at the distance, and at the same time strain to see the latter. + To produce an oblique divergent squint, look at a point below and to one side of an object at the distance while straining to see the latter. When successful two images will be seen arranged horizontally, vertically, or obliquely, according to the direction of the strain. The production of convergent squint is usually easier than that of the other varieties, and most patients succeed better with a light as the object of vision than with a letter, or other non-luminous object. SQUINT AND AMBLYOPIA: THEIR CURE By W. H. BATES, M. D. Squint, or strabismus, is that condition of the eyes in which both are not directed to the same point at the same time. One eye may turn out more or less persistently while the other is normal (divergent squint), or it may turn in (convergent squint), or it may look too high or too low while deviating at the same time in an outward or inward direction (vertical squint). Sometimes these conditions change from one eye to another (alternating squint), and sometimes the character of the squint changes in the same eye, divergent squint becoming convergent and vice versa. Sometimes the patient is conscious of seeing two images of the object regarded, and sometimes he is not. Usually there is a lowering of vision in the deviating eye which cannot be improved by glasses, and for which no apparent or sufficient cause can be found. This condition is known as amblyopia, literally dim-sightedness, and is supposed to be incurable after a very early age, even though the squint may be corrected. Operations, which are now seldom advised, are admitted to be a gamble. According to Fuchs,1 "their results are as a rule simply cosmetic. The sight of the squinting eye is not influenced by the operation, and only in a few instances is even binocular vision restored." This is an understatement rather than the reverse, for a desirable cosmetic effect cannot be counted upon, and in not a few cases the condition is made worse. Sometimes the affected eye becomes straight and remains straight permanently, but often, after it has remained straight for a shorter or a longer time, it suddenly turns, in the opposite direction. I myself have had both failures and successes from operations. In one case the eyes not only became straight, but binocular single vision—that is, the power of fusing the two visual images into one—was restored, and when I last saw the patient, thirty years after the operation, there had been no change in these conditions. Yet when I reported to the ophthalmological section of the New York Academy of Medicine that I had cut away a quarter of an inch from the tendon of the internal rectus of each eye, the members were unanimous in their opinion that the eyes would certainly turn in the opposite direction in a very short time. In other cases the eyes, after remaining straight for a time, have reverted to their old condition, or turned in the opposite direction. The latter happened once after an apparently perfect result, including the restoration of binocular single vision, which had been permanent for five years. The consequent deformity was terrible. Sometimes I tried to undo the harm resulting from operations, my own and those of others, but invariably I failed. Glasses, prescribed on the theory that the existence of errors of refraction is responsible for the failure of the two eyes to act together, sometimes appear to do good; but exceptions are numerous, and in many cases they fail even to prevent the condition from becoming steadily worse. The fusion training of Worth is not believed to be of much use after the age of five or six, and often fails even then, in which case Worth recommends operations. Fortunately for the victims of this distressing condition, their eyes often become straight spontaneously, regardless of what is or is not done to them. More rarely the vision of the squinting eye is restored. If the sight of the good eye is destroyed, the amblyopic eye is very likely to recover normal vision, often in an incredibly short space of time. In spite of the fact that the text-books agree in assuring us that amblyopia is incurable, many cases of the latter class are on record. The fact is that both squint and amblyopia, like errors of refraction, are functional troubles, originating entirely in the mind. Both can be produced in normal eyes by a strain to see, and both are immediately relieved when the patient looks at a blank surface and remembers something perfectly. A permanent cure is a mere matter of making this temporary relaxation permanent. Permanent relaxation can be obtained by any of the methods used in the cure of errors of refraction, but in the case of young children who do not know their letters these methods have to be modified. Such children can be cured by encouraging them to use their eyes on any small objects that interest them. There are many ways in which this can be done, and it is important to devise a variety of exercises so that the child will not weary of them. For the same reason the presence of other children is at times desirable. There must be no compulsion and no harshness, for as soon as any exercise ceases to be pleasant it ceases to be beneficial. The needle, the brush, the pencil, kindergarten and Montessori material, picture books, playing cards, etc., may all be utilized for purposes of eye training. At first it will be necessary to use rather large objects and forms, but as the sight improves the size must be reduced. A child may begin to sew, for instance, with a coarse needle and thread, and will naturally take large stitches. As its sight improves a finer needle should be provided, and the stitches will naturally be smaller. Painting the openings of letters in different colors is an excellent practice, and as the sight improves the size of the letters can be reduced. Map drawing and the study of maps is a good thing, and can be easily adapted to the state of the vision. With a map of the United States a child can begin by picking out all the states of a particular color, and as its sight improves it can pick out the rivers and cities. In drawing maps it can proceed in the same way, beginning with the outlines of countries or states, and with improved vision putting in the details. A paper covered with spots in various colors is another useful thing, as the child gets much amusement and benefit from picking out all the spots of the same color. With improved vision the size of the spots can be reduced and their number increased. Many interesting games can be devised with playing cards. "Slap Jack" is a good one, as it awakens intense interest and great quickness of vision is required to slap the Jack with the hand the moment its face appears on the table. These ideas are only suggestions, and any intelligent parent will be able to add to them. Both children and adults are greatly benefited by making their squint worse or producing new kinds of squint (see page 2). The voluntary production of squint is a favorite amusement with children, and if they show an inclination to indulge in it, they should be encouraged. Most parents fear that the temporary squint will become permanent, but the fact is just the contrary. Anyone who can squint voluntarily will never squint involuntarily. Avoid using effort, force to keep a squint eye straight. This leads to more strain, eye muscle tension, abnormal eye movement. Use relaxation. HOW I CURED MY CHILD OF SQUINT By MRS. B. F. GLIENKE The following remarkable story is published in the hope that it may help other parents in the treatment of squinting children. The patient was first seen on April 24, 1920, her age being four years. When her sight was tested with pothooks her eyes were straight and her vision normal. When tested with the letters of the Snellen test card, which she could not read, or with figures, which she did not know, her eyes turned, and the retinoscope showed that she had compound myopic astigmatism. When she looked at a blank wall without trying to see, her eyes were again straight and her vision normal. When my little daughter was quite young I noticed that her eyes were crossed at times, while at others they were perfectly straight. Later the squint became more continuous, and when she was four years old she was taken to Dr. Bates. He said the trouble was entirely a nervous one, and called my attention to the fact that when the child was comfortable and happy her eyes were straight, and when she was nervous they turned. He said that she should be encouraged to use her eyes as much as possible on objects that interested her, and that she must never be scolded or punished. He also recommended a cold sponge bath and massage first thing in the morning, for the purpose of quieting and strengthening her nerves and improving her general health. As I had been a teacher of drawing before my marriage and understood something of kindergarten methods, I did not find it difficult to follow his instructions. I drew pictures of animals, and asked Marie to tell me if they were running, walking, or standing still, whether they were looking at her, or facing in some other direction, whether they had four legs or two. I showed her a picture of the moon, and asked her to tell me whether the horns were pointing upward, downward, or sideways. We played that the moon was full of water and had to be held right side up so that the water would not run out. She became very much interested in these pictures, and as long as the interest lasted her eyes were straight. When they ceased to interest her the squint returned. Sometimes I would ask her to look at the windows and tell me whether they were open at the top or bottom, whether the shades were partly down, or all the way down. Then we would look at the windows across the street and do the same thing. We also watched the passing motors, and I asked her to tell me how many people there were in them and whether these people were men, women or children. We studied the patterns of the wall paper, and when visitors came I asked her after they had gone to tell me what kind of clothes they had on. I taught her to sew and paint, to match colors, and braid mats, to thread beads, and do things with building blocks. Her father, who is a printer, showed her specimens of diamond type, and of minion which is even smaller than diamond. She enjoyed picking out the smallest letters, and when she did so her eyes were straight. Threading beads was the most beneficial work undertaken, its tediousness being overcome by the fact that the child's doll and all her stuffed animals, Teddy bear, bunny, dog, etc., each received its own particular necklace of beads. The cold baths and massage were also a great help. The combined results of the treatment were wonderful. Her eyes began to be straight all the time. Her nervous condition and her appetite improved, and she slept better. Then we had some set-backs. First she had an attack of grippe with cough, headaches and fever. The squint came back and stayed with her for several weeks, until she was well. Then her eyes became straight again. Later on when she was playing with her little brother they disagreed about something, and Marie got so nervous that her eyes became worse than on any previous occasion since she had been under treatment. The squint alternated from one eye to the other, the left eye being the worse, and next day we were very much worried when we found that the left eye was practically blind. But we went on encouraging her to use her eyes, and in ten days she was as well as ever. STORIES FROM THE CLINIC 9: Three Cases of Squint By EMILY C. LIERMAN One day as I entered the clinic I saw two mothers standing side by side, each holding a little boy by the hand. The children were both about the same age, five years, and both were cross-eyed; but there the resemblance ceased. One seemed happy and contented, and it was quite evident that he was much loved and well cared for. Although cheap and plain, the clothes of both mother and child were clean and neat, and often the boy would look at the mother for a smile, which was always there. The other boy was plainly unhappy and neglected. I could read the mind of the mother, who was anything but clean, as she stood there grasping his hand a little too tightly, and even without her frequent whispered threats of dire things to happen if the child did not keep still, I would have known that she considered him a nuisance, and not a precious possession as boy No. 1 plainly was to his mother. I was at a loss to know which child to treat first, but decided upon Nathan, the clean one, and tried to keep the other interested while he waited. Nathan had beautiful black curls, and should have been pretty, but for the convergent squint of his right eye, which gave him a very peculiar appearance. His vision was very poor. With both eyes together he could read at ten feet only the fifty line of the test card, and with the squinting eye he read only the seventy line. I showed him how to palm, and while he was doing so I had time to talk to his mother. She said that his right eye had turned in since he was two years old and that all the doctors she had taken him to had prescribed glasses. These, however, had not helped him. I now asked Nathan to read the card again, and was delighted to find that the vision of the bad eye had become equal to that of the good one, namely 10/50. I had difficulty in keeping his head straight while I was testing him, for like most children with squint, he tried to improve his sight by looking at the object of vision from all sorts of angles. After he had palmed for a sufficient length of time, however, he became able to correct this habit. The extraordinary sympathy which existed between mother and child came out again during the treatment, for no matter what I said or did, the child would not smile until the mother did. Nathan came to the clinic very regularly for a year, and for the first six months he always wore a black patch over his better eye, the left, while atropine was also used in this eye to prevent its use in case the patch was not worn constantly. Nathan did not like the patch, and his mother had to promise all sorts of things to keep it on. After it was removed the atropine was continued. Dr. Bates had told me what to expect when the patch was removed, and so I was not shocked to see the eye turn in. I knew the condition would be temporary, and that in time both eyes would be straight. Treatment was continued for six months, and now the boy reads at times 10/15 with both eyes, and always with a smile. The dirty little boy, to whom we must now go back, was called George, and his condition was worse than that of Nathan, for he had squint in both eyes. At ten feet he read the fifty line, but complained that he saw double. I showed him how to palm, and while he was doing so his mother told me how very bad he was, adding that I must spank him if he did not mind me. "I think he gets enough of that already," I said, but I was careful to say it with a smile, fearing that she might lose her temper and say more than I would like. George had now been palming five minutes, and I asked him to uncover his eyes and look at the card. He was much surprised to find that he could read the forty line without seeing the letters double. I asked his mother very quietly to be a little patient with him and help him at home, and I gave her a test card for him to practice with. "Madam," she replied, "I am the mother of six, and I haven't time to fuss with him." "No wonder the kiddy is cross-eyed," I thought, and seeing I could get no help in that quarter, I appealed to George. When I revealed to him the possibility of a Christmas present if he came to the clinic regularly and did what I told him he became interested. I did not know how much could be done for his eyes in the eight weeks that remained before the holidays, but I felt sure that with his co-operation we could at least make a good start. This he gave me in full measure. Never did I have a more enthusiastic patient. He came to the clinic regularly three days a week, and often when I came late I would find him waiting for me on the hospital steps and yelling: "Here she is. I saw her first." After he had been practicing faithfully for two weeks—palming six times a day, and perhaps more, according to his own report—he was able to keep his eyes straight while he read the test card at twelve feet. After he had done this I asked him to spell a word with four letters, and instantly his eyes turned. I had him palm again, and then I asked him to count up to twenty. His eyes remained straight, because he could do this without strain. Two days before. Christmas I brought my bundle of presents for the children. George was there bright and early, and with him had come three of his brothers, to get their share too, "if there was any," as George explained. Fortunately a little fairy had prepared me for this, and I had gifts for everyone. That day George was able to keep his eyes straight both before and after his treatment, and to read 15/10 with each eye separately. I have never seen him since, and can only hope that he kept up the treatment until permanently cured. When little Ruth, aged three, first came to us Dr. Bates suggested to her mother, who was nearsighted, that she should have her own eyes cured, because her condition had a bad effect on the child. She consented, and now has nearly normal vision. Ruth had squint and was so tiny that I had to put her on a table to treat her. As she could not, of course, read the letters on the test card, I held before her a card covered with E's of various sizes turned in different directions. Her mother was quite positive that she couldn't understand what I wanted her to do, but Ruth, as often happens in such cases, had more intelligence than her mother gave her credit for. I asked her to tell me whether a certain E pointed upward, or to the right or left, by merely indicating the direction with her finger, and it did not take an instant for her to show Mother how bright she was. I showed her how to palm, and in a little while she indicated correctly the direction of the letters on several lines. When the letters became indistinct, as I moved the card further away, she became excited and wanted to cry, and her left eye turned in markedly. She palmed again and while she was doing so, I asked her all about her dolly, whether her eyes were blue, or some other color, what kind of clothes she wore, and so on. When she removed her hands from her eyes both were straight. Her mother was instructed to practice with her many times a day at short intervals, so that she would not tire of it, and in three months her eyes were straight every time I tested her sight. I was much interested to learn from her mother that if Ruth's daddy raised his voice in the slightest degree when he spoke to her, her eyes were sure to turn in. This merely confirmed my own experience that it is necessary to treat children who have defects of vision with the utmost gentleness if one wants to cure them. Ruth is not cured yet, but she hopes to be before Christmas, because Santa Claus is sure to visit Room 6, Harlem Hospital Clinic, and he does not like to see children squinting. QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS All readers of this magazine are invited to send questions to the editor regarding any difficulties they may experience in using the various methods of treatment which it recommends. These will be answered as promptly as possible. Kindly enclose a stamped addressed envelope. Q - Can opacity of the cornea be cured?—E. B. A - Yes. A patient with opacity of the cornea came to the eye clinic of the Harlem Hospital with a vision of 20/70, and in half an hour became able to read 20/40. Later his vision became normal, much to my surprise. Other cases have also been cured. Q - Is retinitis pigmentosa curable?—R. V. A - Yes. See Better Eyesight, for April, 1920. Q - My eyes are weak, and cannot stand the light. Can anything be done for them?—Mrs. W. T Close vision cure Q - Is it possible to regain the ability to read without glasses when it fails after the age of forty, the sight at the distance being perfect? If so how can this be done?—H. C. A - The failure of the sight at the near-point after forty is due to the same cause as its failure at any other point and at any other age, namely strain. The sight can be restored by practicing at the near-point the same methods used to improve the vision at the distance—palming, shifting, swinging, etc. The sight is never perfect at the distance when imperfect at the near-point, but will become so when the sight at the near point has become normal. A - Yes. Stop wearing dark glasses, and go out into the bright sunshine. As they get stronger accustom them to the direct light of the sun. Let the sun shine on the closed eyelids. Then gradually open them until able to keep them wide open while the sun shines directly into them. Be careful not to overdo this, as much discomfort and lowered vision might result temporarily from a premature exposure of the eyes to strong light. See Better Eyesight for November, 1919. November, 1920 1 -Textbook of Ophthalmology, authorized translation from the twelfth German edition by Duane, p. 795. STORIES FROM THE CLINIC 21: More Cases of Squint By EMILY C. LIERMAN ONE day in the early part of September there came to our clinic a very neatly dressed woman of forty-five, with her daughter, aged eleven. One of the doctors from another section of the dispensary had told her of the wonderful cures wrought by Dr. Bates' methods, and convinced her that they would be effective in the case of her daughter, who was suffering from convergent squint of the left eye. I at once became more than usually interested in this case, not only because I did not want to disappoint the doctor who had sent it, or cause him to lose faith in our methods, but because Selma, the patient, was a dear little girl and made a strong appeal to my sympathies. I did not notice until her eyes became straight that Nature had intended her to be very pretty; but I saw her sweet smile, and her absolute faith in my ability to cure her, combined with her willingness to do as she was told, was very touching. I tested her sight with the Snellen test card, and at ten feet she was able to read, with the right eye, only the forty line. With the left eye (the squinting one) she read only the 200 line. I showed her how to palm, and then I had a talk with the mother, who was wearing glasses, and had been wearing them, as she told me, for twenty-five years. I explained to her how hard it would be to cure her daughter if she continued to wear them. "How can I possibly harm my little girl by wearing glasses?" she asked. You are under a constant strain while you wear them," I answered, "and that affects your daughter's nerves." "But I cannot sew, read, or do other things, without my glasses," she said: "so what shall I do?" I told her to watch very closely while I was treating Selma and do just exactly what she did. She took off her glasses at once, and did not seem to doubt that she would be cured. For this I was very grateful, as mothers are not always willing to take off their glasses at their first visit, thinking, I suppose, that although I may be able to cure children, I cannot cure adults. I placed the mother where she could watch her daughter's eyes during the treatment and, as she saw them after five or ten minutes become temporarily straight, she expressed her gratitude in no uncertain terms. On leaving she invited me to her home, and every time she carne after that the invitation was repeated. She bought a test card, too, for home practice, and Selma was very faithful about using it. From that time up to the present writing mother and daughter have come regularly three days a week. Selma now reads the twenty line with her left eye at twelve feet, and with her right eye, at the same distance, she can read the ten line. Except when she becomes excited or over-anxious, her left eye is straight most of the time. The improvement in the mother's sight seems almost equally remarkable. She reads and sews without her glasses, the lines in her face caused by strain have disappeared, and she looks so much younger that she might easily be taken for her daughter's sister. We have all become fast friends and, although I shall be glad when Selma is completely cured, I will be sorry not to see her smiling face any more at the clinic. At the beginning of the treatment Selma's mother could not be encouraged to discuss other treatment she had had; but when, one day recently, the child read the whole of the test card with both eyes straight, she began to talk. "You don't know how grateful I am to you," she said. "It is not so long ago that I was told at another eye clinic that Selma would have to be operated on for squint. They told me that it would get worse if they didn't operate. I told them to give me time to think it over. I was a whole year thinking it over; but I could not make up my mind to the operation, as I had doubts about its curing her." Doris, aged four, has convergent squint of the right eye, and came to us also during September. It was noticed when she was two years old that the right eye was turning in and, although glasses were immediately secured for her, they did no good. When I first saw her the vision of the squinting eye was only one-quarter normal (10/40), while that of the other eye was one-half normal (10/20). Now the sight of both eyes is slightly above normal (12/10). Doris does not know the alphabet; so in treating her I have to use a card covered with letter E's arranged in different ways, and she tells me which way they are facing, left, right, up or down. I found it rather hard at first to get her to palm for any length of time; but one day the mother told me of a dear baby brother at home, and I told Doris to think of her brother when she closed and covered her eyes. This worked like a charm. When she thinks it time to open her eyes, usually about a minute, she calls out, "Open them?" If I answer, "No," she keeps them closed until I say, "Ready." During the first few treatments the right eye would not keep straight for more than half a minute, but now it stays straight all the time she is reading the chart, down to the ten line. After the treatment it turns in again, but not so badly as before, and if she is reminded to make it look straight she can do so very readily. The child's mother has been a great help in the treatment, both at home and at the clinic, and I think she has got a great deal of good out of it for herself. She is a most unselfish parent, absolutely devoted to her children; but this devotion causes her to get excited and nervous, so that when she arrives at the clinic her eyes are staring almost out of her head. In a few moments she becomes relaxed, and her eyes begin to look natural. Doris got on so nicely that her cousin Arthur, who also has a convergent squint, came for treatment. When I tested his sight I found that the vision of the squinting eye, the left one, was only 10/50, while that of the right eye was 10/20. He was a very bright boy, very obedient and lovable, and when he looked at the chart it was sad to see the left eye turn in until it was almost hidden. He made rapid progress, however, and his mother, who always comes with him, is very happy over the good results obtained in little over a month. At his first visit he was told, after reading a line of letters on the chart, to remember the last letter while he closed and covered his eyes. When he looked at the card again he was able to read another line. His vision now is almost normal, 12/15, and when he is reading the card his eyes are almost straight. His mother tells me that he gets on much better at school than he used to. He is eager to get well, and is very happy when clinic day comes so that he may have another treatment. I am wondering which of the trio will be cured first, and when they are I will give most of the credit to the mothers, for it is their help and the treatment given at home that has counted most. Stories from the Clinic By EMILY C. LIERMAN A CASE OF DIVERGENT SQUINT ONE day a young colored woman came to us with her little boy age nine years. Every time she looked at him it was plainly a look of disgust. The boy had the most wistful face I ever saw. He kept looking up into his mother's face and his expression was that of a deaf and dumb person. One of his eyes seemed to be looking a way off to the opposite side of the room while the other eye was looking straight at her. When his other eye turned to look at her the former would turn out in the opposite direction away from her. He had alternate divergent squint. My heart went out to James as his mother related to me the fact that her other three children had normal sight while James looked so horrible with his crooked eyes. A chill went through me when I heard her say, "I wish he had never been born." Then with more disgust in the sound of her voice she said, "I can't help it, but I hate him." Can anyone imagine a mother disliking her own child so much? All because his eyes were crooked. Complaints came to her from the school he attended. His teacher complained that he was stupid. All this time the little fellow looked up at his mother without moving an eyelid apparently. Her question was, "What can be done with him or for him? Can you give him glasses or operate to cure his eyes?" I told the mother that glasses would never cure his squint and neither would an operation. I asked her to watch carefully and see what James was about to do for me. First, I held him very close to me and patted his woolly head. He pressed a little closer for more. He liked the beginning of his treatment. I asked him to say the alphabet for me, but he said he could not remember all of the letters. He stood ten feet from the test card. I asked him to read, starting with the largest letter at the top. He read a few letters correctly but I soon found out that he did not know many letters of the alphabet. His mother remarked then that the teacher in school thought his mind was affected because of his eyes and that there was little hope of curing him. I had my doubts about the teacher saying such a thing but I did not say so to the mother. What a pity it was to have the dear little fellow hear all this. He looked so worried and restless. Perhaps he wanted to run away somewhere because his eyes caused others so much trouble. I taught him to palm, telling him to remember a small Bible class pin I was wearing on my dress. In a few minutes I tested his sight with the E card, which is used always in cases where children do not know their letters. At ten feet he saw the fifty line. Again I told him to palm, and asked his mother not to speak to him while he was resting his eyes. In the meantime I attended to other patients. After a few moments I glanced at him and saw two big tears rolling down each cheek. He was weeping silently. His mother was just about ready to find fault with him, but I intervened and walked her gently out of the room to a bench outside the door. I whispered to James that I loved him a whole lot and if he would learn to read his letters at home and could read half of the test card correctly the next time he came, I would give him a nickel. I saw him smile, and when I was able to treat him again I found that his sight had improved to the forty line of the E card. I have been wondering ever since whether it was the Bible class pin on my dress which he was asked to remember or was it a clear vision he had of that nickel I had promised him that improved his sight for the forty line of letters. Two days later James appeared again with his mother and both were smiling. He could hardly wait to tell me that he knew his letters perfectly. His big brother taught him at home, he said, and he hoped I would be pleased as his teacher was, when he read all his letters on the blackboard for her that day. It was amusing to see James looking toward my purse which was hanging on the wall in the Clinic room. He was thinking of that nickel I promised him. I produced a strange test card which he had not seen. When he began to read the card I placed him fifteen feet away, which was five feet further than the first day. He was so excited that his squint became worse and he could not read. Dr. Bates said his trouble was mostly nervousness. I told him to palm again and reminded him of the letter E with its straight line at the top and to the left, with an opening to the right. Then he became able to see the letters after a few moments' rest. I called Dr. Bates' attention to the sudden improvement in his eyes as he read one line after another until he reached the thirty line, when suddenly his eyes turned out again, but after he had rested his eyes again they became straight. I gave him the promised nickel that day, which made him very happy. James was able to keep his eyes straight most of the time after he had been coming to the Clinic for a month. The attitude of his mother toward him was decidedly better and she promised to help him with the treatment of his eyes at home. I do not know whether James was entirely cured or not because our work at the Harlem Hospital Clinic has since been discontinued. Squint (Strabismus, Crossed, Wandering Eyes) By W. H. BATES, M.D. SQUINT is a condition of the eyes in which both eyes do not regard one point at the same time. It is very common, and more prevalent among children than adults. Many cases improve with advancing years, while others may become worse. Squint may occur at the same time with myopia, astigmatism, or hypermetropia, or with any disease of the inside of the eye. Symptoms In squint, one eye does not look in the same direction as the other. For example, the left eye may look straight at the Snellen test card with normal vision, while the right eye may turn in toward the nose, and have imperfect sight. The squint is variable in some cases. At times it may be less or disappear altogether, while at other times it may be more pronounced. In some cases of squint, the patient is conscious of the strain. When the eyes turn in, he may be conscious that his eyes are not straight. When the eyes are nearly straight, he is usually able to realize that the eyes are not so strained. Cause The cause of squint in all cases is due to strain. When the eyes are under one kind of strain, they may turn in, and with a different strain, they may turn out, or one eye may be higher than the other, all caused by strain. The relief or cure of one kind of strain relieves or cures all forms of strain. Squint in any form is always benefited by rest. Various Cures for Crossed/Wandering Eyes Rest The best treatment for squint is mental rest. Many patients with squint suffer very much from eyestrain. By closing the eyes and resting them, or by palming for a few minutes or longer, about ten times a day, most of these cases are cured without other treatment. Patch In many cases, the squinting eye has imperfect sight. When the eyes are examined with the ophthalmoscope, no change can usually be discovered in the retina. Such cases have what is called "amblyopia ex anopsia." Some cases are benefited by wearing a patch over the good eye, so that the patient is compelled to use the squinting eye for vision. After several weeks or months, the vision of the squinting eye may become normal by constantly wearing a patch over the good eye. Many cases of squint are cured in this way. Swinging The strain, from which so many of these patients suffer, is benefited by the swing. Almost all squint cases can be taught to imagine, while the good eye is covered, that stationary objects are moving. In cases where the swing of stationary objects is not readily accomplished, any of the following methods may be effective: 1. The forefinger is held about six inches in front of the face, and a short distance to one side. By looking straight ahead and moving the head from side to side, the finger appears to move. This movement of the finger is greater than the movement of objects at the distance, but, by practice, patients become able to imagine not only the finger to be moving, but also distant objects as well. 2. The patient may stand about two feet to one side of a table on which an open book is placed. When he steps one or two paces forward, the book and the table appear to move backward. When he takes two or more steps backward, the table and the book appear to move forward. 3. The patient stands in front of a window and looks at the distant houses. By swaying his body from side to side, the window, the curtains, or the curtain cord may be imagined to be moving from side to side, in the opposite direction to the movement of his body, and the more distant objects appear to move in the same direction that he moves his head and eyes. 4. The patient stands ten feet or less from the Snellen test card and looks to the right side of the room, five feet or more from the card. When he looks to the right, the card is always to the left of where he is looking. When he looks to the left side of the room, the card is to the right of where he is looking. By alternately looking from one side of the card to the other, the patient becomes able to imagine that when he looks to the right, everything in the room moves to the left. When he looks to the left, everything in the room appears to move to the right. After some practice, he becomes able to imagine that the card is moving in the opposite direction to the movement of his eyes. This movement can be shortened by shortening the movement of the eyes from side to side. (Oppositional movement) 5. When the patient regards the Snellen test card at fifteen feet or nearer, and looks a few inches to the right of the big "C", the letter is always to the left of where he is looking. When he looks a few inches or further to the left of the "C", it is always to the right of where he is looking. By alternately looking from right to left of the "C", he becomes able to imagine it to be moving in the opposite direction. By shortening the distance between the points regarded, the swing is also shortened. The patient is encouraged to practice this swing with the good eye covered. When the swing is practiced correctly, there is always a benefit to the vision and squint. Practice shifting left and right on the letter E. Memory Some patients are very much benefited by being encouraged to remember the letters on the Snellen test card perfectly, i.e., to remember the black part of the letter perfectly black and the white part perfectly white. When the memory is perfect, it is possible for the imagination to be perfect. This being true, the patient becomes able, by practice, to imagine he sees each and every letter of the Snellen test card, and to imagine them to be moving. The movement of the swing can be stopped by staring at one point of a large or small letter, with the result that the vision is always lowered and the squint becomes worse. When the patient becomes able to imagine known letters perfectly, he is soon able to imagine the letters of a strange card perfectly. When the letters are imagined perfectly, they are seen perfectly. Practice with a familiar card, or with a card whose letters are remembered, is one of the best methods known for curing the imperfect sight of squint and the squint itself. Central Fixation Another satisfactory method is to have the patient practice central fixation, or seeing best where he is looking, and seeing worse where he is not looking. In practicing central fixation, it is necessary for the patient to shift constantly and to blink frequently. To teach a patient central fixation, his attention is called to the fact that when he looks at the top of the card, he can distinguish the large letters, but the letters on the bottom of the card cannot be distinguished. When he looks at the bottom of the card, he sees the small letters where he is looking, better than the large letters on the upper part of the card, where he is not looking. Eccentric Fixation Some patients have what is called "eccentric fixation", which is the opposite of "central fixation." Such patients see best where they are not looking. Eccentric fixation can always be demonstrated to be present when the vision is imperfect, or when the squint is manifest. To cure eccentric fixation, it is necessary to demonstrate these facts, and by practicing with the small letters, the results are usually good. The patient is told to look at the first letter on the bottom (left) line of the Snellen test card, which may be read at ten feet or nearer, and have him note that the letters toward the right end of the line are blurred or not seen at all. By alternately shifting from the beginning of the line to the end of the line and back again, the vision is usually improved, because eccentric fixation is lessened by this practice. Sometimes, it is necessary for the instructor to stand behind the card and watch the eyes of the patient, who may look a foot or more away from the letter that he is requested to regard with the squinting eye, while the good eye is covered. He may look a foot above or a foot below, or at some point a foot or more away from the letter which he is asked to regard. The instructor is usually able to tell when the patient is not looking at the letter desired. The instructor directs the patient to look down when he sees that the patient is looking too far up. The patient is directed to look to the right, when it is observed that he is looking too far to the left, and by watching him closely, the eccentric fixation can be corrected to such an extent that the vision becomes normal and the squint disappears. Persons that have cataracts, macula degeneration, extreme blur and other vision impairments develop the destructive habit of eccentric fixation: to use the peripheral field of the retina, peripheral field of vision to see a object. This increases eye muscle tension… vision impairment. Central fixation and shifting cures this incorrect eye function. Fixing Eye A great deal has been said about the "fixing eye" in squint, i.e., the eye that looks straight. Sometimes the vision of the squinting eye may be very poor, and one would expect the patient to focus with the eye that has better vision. This is not always the case, because some patients with a high degree of myopia in the left eye will turn the right eye in and look straight with the left eye. These cases are very interesting, no two are exactly alike and one needs to study the individual case in order to obtain the best results. Imagination There are some rare cases where the vision is perfect in each eye, and yet the patient will suffer from squint. One may have considerable difficulty in finding the method of treatment which will cure or relieve these cases. One of the best methods is to have the patient practice the imagination cure. The patient can look at a page of a book twenty feet away and not read any of the letters. If the letter "O" is the second letter of the fourth word and on the 10th line, the vision may not be good enough for the patient to recognize the letter, but he may become able to imagine it. If he imagines that the left side is straight, it makes him uncomfortable and the left side is not imagined perfectly black. If he imagines that the left side is curved, he feels comfortable and the left side appears clearer and blacker. By imagining each of the four sides of the letter "O" perfectly, the imagination of the letter is improved, but if one or more sides are imagined imperfectly, the patient is uncomfortable and the vision or the imagination of the "O" becomes imperfect. Some patients are able to imagine perfectly and are conscious when they imagine imperfectly. In one case, a girl eleven years of age was able to look for half a minute at diamond type which was placed ten feet away, at a distance where the patient could not distinguish the letters. She then closed her eyes, palmed, and imagined correctly each letter that her mother designated. For example, her mother picked out the capital letter "M", the first letter of the fourth word on the 10th line. While palming with her eyes closed, the patient imagined the left side straight, the right side straight, the top open and the bottom open. I asked her if it could be an "H." She answered that it could, but that she could imagine an "M" better, which was correct. Some patients are able to use their imagination correctly and imagine small letters just as well as capital letters. In order to obtain perfect results, it is necessary that the eyes be perfectly relaxed, and when the eyes are relaxed, all the nerves of the body are also relaxed. Those cases of squint which become able to do this are soon cured. Imagination of crossed images with the eyes closed is characteristic of divergent squint, i.e., squint with the eyes turned out. The patient imagines the crossed images alternately with the eyes open and with the eyes closed. When, by practice, the imagination becomes as good with the eyes open as with the eyes closed, the squint is usually corrected. Double Vision (Effective Cures for Squint: Imagining, Controlling Double Images) After (in the event that) the usual treatment of squint has failed, it is well to teach such cases to see double. When the right eye turns in toward the nose and the left eye is straight, the letter or other object seen by the left or normal eye, is seen straight ahead, while the image seen by the right or squinting eye, is suppressed by an effort and is not seen at all. To teach the patient to see with both eyes at the same time requires much time and patience. When double vision is obtained, the image seen by the right eye is to the right, while the image seen by the left eye is to the left. We say that the images are seen on the same side as the eye which sees them. With the eyes closed, the patient is taught to imagine a letter, object or a light to be double, each image imagined to be on the same side as the eye with which the patient imagines he sees it. With an effort, the two images may be made to separate to any desired extent. By repeatedly imagining the double images with the eyes closed, the patient becomes able, with the eyes open, to imagine the double images to be separated a few inches or less, a foot apart or further. Patients become able not only to imagine images with the eyes closed, apparently seen on the same side as the eye which imagines them, but also—and this suggests curative treatment—to imagine crossed images, that is, the right eye image is imagined to the left, while the left eye image is imagined to the right. With one or both eyes turned in, each of the double images is imagined on the same side as the eye which imagines it. When the images are crossed, the convergent squint is over corrected and the eyes turn out. All this can at first be accomplished more readily with the eyes closed than with them open. When the patient controls the separation of the images with the eyes open as well as with the eyes closed, the squint is benefited. Case Reports I. A boy, two years of age, had developed squint in his right eye several months before I saw him. He was just beginning to walk. At his first visit, I took hold of his hands and swung him round and round, until his feet were off the floor, and had him look up toward the ceiling. While doing this, his eyes became straight. The father and mother also took turns in swinging the child, and when he looked up into their faces, his eyes were straight. Every day, one or more members of the family would swing the boy around for at least five minutes. A year afterwards, the squint had not returned. Swing the child around in a circle counter clockwise, clockwise, counter clockwise… II. A girl, aged fourteen, had an internal squint of the right eye. The vision of this eye was very poor, and she was unable to count fingers at one foot from that eye. The vision of the left eye was normal. She was encouraged to use her right eye by covering the left with a patch. She did not like the patch, so the lenses were removed from their frame, and an opaque glass was placed in the frame for the left eye. The girl was very nervous and wearing the glass gave her continual trouble. Her playmates teased her so much that she deliberately dropped them in the snow. Her father talked to her and insisted that she wear the frame with the opaque glass all the time. When she realized that she must keep the good eye covered until she was cured, her vision immediately began to improve. In less than a week, she became able to read the ten line on the Snellen test card at twenty feet with each eye. She also became able to read fine print with the right eye, just as well as she could with the left. The realization that she would have to wear the glass until she was cured was an incentive for her to practice those methods which improved her sight. When she looked at the Snellen test card at one foot, and remembered that the large letter at the top was a "C", with the aid of her imagination, she became able to see the "C." When she closed her eyes and remembered a better "C", she was able, with her eyes open, to imagine it at a greater distance, three feet. In a short time, her vision improved to 20/200 by alternately remembering a better "C" with her eyes closed, and imagining it as well as she could with her eyes open in flashes. Palming was a help and improved her vision to 20/40. A few days later, her vision had improved to 20/20 with the aid of the swing. III. A young woman, twenty-four years of age, called to see me about her left eye which was causing her more or less pain. The left eye became very much fatigued when she tried to read. Her vision in that eye was 20/40. Her right eye had no perception of light and was turned in. A great many doctors had told the patient that the blindness was hopeless, and that nothing could be done to improve the vision of the right eye. I had the patient practice the usual relaxation exercises, swinging, palming, ect. The vision of the left eye improved very rapidly, and, much to my surprise, the vision of the right eye also improved. After two weeks, during which the patient had received about six treatments, the vision of both eyes became normal. The right eye which had had no perception of light was sensitive now to a light reflected from the ophthalmoscope into her pupil. The pupil of the right eye always contracted when the light was turned into either eye. The squint disappeared and she was able to see the same object, with both eyes, at the same time. Avoid Artificial 3-D Magic Eyes pictures; http://cleareyesight-batesmethod.info/id103.html They cause strabismus, double vision. Ophthalmologist Bates BETTER EYESIGHT MAGAZINE with Translator, Speaker; https://www.cleareyesight.info/naturalvi...atesmethod - FREE Bates Method Natural Vision Improvement Training, 20 Color E-books. YouTube Videos; https://www.youtube.com/user/ClarkClydeN...rid&view=0 - Phone, Google Video Chat, Skype Training; https://cleareyesight-batesmethod.info |

|||

|

« Next Oldest | Next Newest »

|

User(s) browsing this thread: 1 Guest(s)

Search

Search Member List

Member List Calendar

Calendar Help

Help