|

Retinitis Pigmentosa

|

|

07-10-2014, 08:12 PM

(This post was last modified: 07-11-2014 07:48 AM by ClarkNight.)

Post: #1

|

|||

|

|||

|

Retinitis Pigmentosa

Working on placing cures from Better Eyesight Magazine and other sources, experiences here;

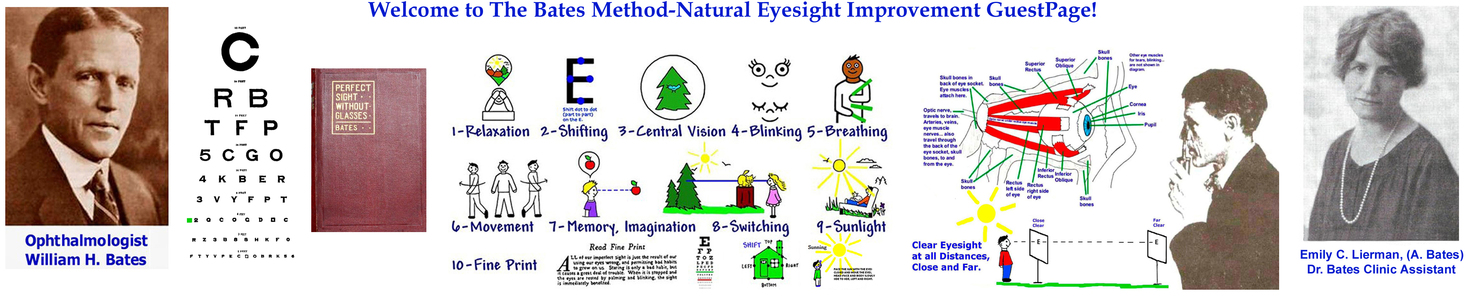

Retinitis Pigmentosa; STORIES FROM THE CLINIC 3. Retinitis Pigmentosa By EMILY C. LIERMAN I am not a physician, and I know very little about the disease of the eyes known as retinitis pigmentosa except how to relieve it. I have been told that in this condition spots of black pigment are deposited in the retina, that parts of the retina are destroyed, and that the nerve of sight is diseased. Eye books which describe the disease say that it usually begins in childhood, and progresses very slowly until it ends in complete blindness. The field of vision is contracted, and, because they cannot see objects on either side of them, patients frequently stumble against such objects. In most cases the vision is much worse at night than in the daytime. The books say further that no treatment is known which helps these cases. Nevertheless Dr. Bates reported, in the New York Medical Journal of February 3, 1917, a case of retinitis pigmentosa which had been materially benefited through treatment by relaxation, and by the use of the same methods, I have been able to greatly improve the sight in several cases of the same kind. My first case of retinitis pigmentosa was Pauline, a little girl of twelve who came to the clinic in October, 1917. At five feet from the card she could read only the seventy line, and her eyes vibrated continually from side to side, a condition known as nystagmus. She was very shy and extremely nervous, and appealed to me pathetically for glasses, so that she could see the blackboard, and the teacher would not think her stupid and make fun of her. I have noticed that eye patients often suffer from extreme nervousness; but this poor child had the worst case of nerves I ever saw, and the slightest agitation made her sight worse. If, in asking her to read a line on the test card, I raised my voice and spoke a little peremptorily, her face would flush, and she would say, "I cannot see anything now." But just as soon as I lowered my voice and took pains to speak gently, her sight cleared up. I began her treatment by telling her to cover her eyes with the palms of her hands and remember the letters she had seen on the card. This improved her sight so much that before she left she was able to see all the fifty line at five feet, and—what thrilled me most of all—the dreadful movement of her eyes had stopped. She came quite steadily to the clinic, and every time she came I was able to improve her sight, so that at last she became able to read the writing on the blackboard at school. Then I did not see her again for six months. When she came back she told me that she had been working in a laundry during the summer because she hated school. She had also been ill during the summer, and her mother had taken her to a hospital for treatment. While she was there an eye specialist had looked at her eyes, and this made her so nervous that they had started to vibrate from side to side. He said to her: "You ought to have your eyes treated; they are very bad." "I am having them treated at the Harlem Hospital Clinic," she answered. "I know how to stop that vibration." Then she palmed for a while and when she uncovered and opened her eyes the doctor looked at them again. "Why they seem all right now," he said. "You had better go to that doctor until you are cured. He can do more for you than I can." I was very much pleased to find that in spite of having stayed away so long, she had not forgotten what I had told her, and was able to stop her nystagmus. I tested her sight, and found that it was no worse than when I had last seen her. In fact, in some ways, it was better. She was not so nervous, and she said that her family and friends noticed that her eyes looked better. She herself was now very enthusiastic and anxious to have me help her. I told her to palm as usual, and left her to treat other patients. Five minutes later she read the thirty line at thirteen feet. I now told her to look first to the right of the card and then to the left, and to note that it appeared to move in a direction opposite to the movement of her eyes, then to close her eyes and remember this movement. She did this, and when she opened her eyes she read two letters on the twenty line. At a later visit she read the whole of the twenty line at thirteen feet. The last patient I treated for this dreadful disease was an old man of seventy. He came to the clinic on January 14, 1920, and when I first saw him, he was standing with many others, waiting patiently for Dr. Bates to speak to him. Our work has to be done very rapidly, because of the very short time we have to treat so many patients, and I very seldom have time to observe individuals as I would like to do. But because of his unusual appearance, I at once singled this dear old man out from the crowd. Most men of his age who come to our clinic are unkempt, dirty and ragged—pitiable objects generally. But this man was well groomed. His clothes, though worn and old, were well brushed; his shoes were polished, his collar clean, his tie neatly adjusted. He had a great abundance of snow-white hair, neatly parted and brushed, and his skin was like a baby's, "pink and white." Dr. Bates asked me to treat him with the usual remark, "See what you can do for this man," and I placed him four feet from the card, asking him to read what he could. "I'm afraid I can't see so well, ma'am," he said; "my eyes bother me a good deal." "I'm going to show you how to rest your eyes so that they won't bother you," I answered. The best he could do at this distance was to read the fifty line. I told him to palm, and in less than five minutes he saw a number of letters on the forty line. The next time he came I put him nine feet from the card, and at this distance he read all the letters on the thirty line. He was so happy and excited over this that I became excited too. I forgot that I had other patients waiting for me and encouraged him to talk, a thing which I am seldom able to do with the patients. I was glad afterward that I did so for he had a wonderful story to tell. "Do you know, ma'am," he said, "for two nights I palmed and rested my eyes for a long time before I went to bed—and what do you think?—I slept all the night through without waking up once. Now I think that's great, ma'am, because for years I have had insomnia. I would sleep only a little while; then I would get up and smoke my pipe to pass the time." At a later visit I put him twelve feet from the card, and at this distance also he was able to read the thirty line. When I told him what he had done he was again greatly pleased and excited. "You know I'm so much better," he said, "that I didn't even notice that I was further away than usual. Thank you, ma'am. God bless you, ma'am." During the practice, when he failed to see a letter I was pointing to, I said: "Close your eyes and tell me the color of your grandchild's eyes." "Blue. ma'am." he said. "Keep your eyes covered, keep remembering the color of baby's eyes." He did this, and after a few minutes his sight cleared up and he saw the letter. After we had finished the practice I again encouraged him to talk, and he told me more about his insomnia. "Do you know, ma'am," he said, "after I had had two night's sleep without waking up I didn't dare tell any of my family about it, for fear that it wouldn't last and I would only disappoint them. So I waited. Now, do you know, ma'am, it is just two weeks that I have slept the night through without waking up once, and so I told my wife about it. She is so happy, ma'am, I just can't tell you, for it has been many years since I was able to do that." I wish I could have a picture of his face when he is telling of the improvement in his eyesight and general health. It would be a picture of gentleness, love, kindness and gratitude. Recently he looked up into my face and said: "I am seeing you better now, ma'am. You look younger." In two months his vision improved from 10/200 to 10/30. As he made but eight visits in this time, I feel that this record is remarkable. I also feel that the statements in the books about the impossibility of doing anything for patients with retinitis pigmentosa are in need of modification. Retinitis Pigmentosa By W. H. BATES, M.D. There are many cases of imperfect sight which are congenital. That is, people are born with different diseases of the eye. Retinitis pigmentosa is usually congenital. The condition is easily recognized in most cases with the aid of the ophthalmoscope. In all cases, the retina is covered, more or less completely, with black areas. These black areas are about 1/30 of an inch in diameter. They are very irregular in size and shape. In severe cases of retinitis pigmentosa, the retina may be covered so thickly by these black specks that the retina cannot be seen. Most cases give a history of poor sight from birth. At first, only a small number of black spots are visible, but after the child is twelve years of age or older, the number of these spots increases gradually. At the same time that these spots are increasing, there are serious changes taking place in the back part of the eye. The optic nerve becomes atrophied, but the atrophy does not increase sufficiently to produce complete blindness. The middle coat of the eyeball is inflamed and produces floating spots in the vitreous (one of the fluids in the back part of the eye). All cases of retinitis pigmentosa acquire cataract before they are thirty years of age. There are exceptions to this rule, however. Some patients acquire retinitis pigmentosa after they are fifty years of age or older. One characteristic of retinitis pigmentosa is that the vision is always changing, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse. One very common symptom that is usually present is night blindness. Treatment for the cure of the night blindness helps retinitis pigmentosa. In some cases myopia is present and it is of a kind which is difficult to cure. It is a prevailing belief that retinitis pigmentosa is incurable and that when it becomes manifest in its early stages, the condition goes on increasing and the blindness becomes more decided. Usually, the blindness does not become permanent. One case of retinitis pigmentosa with myopia was observed. The patient left town and was not seen again for more than six months. She then came into the office to report. Her first words were that her eyes were better. A physician was calling on me at the same time, and he was asked: "Would you like to see a case of retinitis pigmentosa." He replied that he would. Before the doctor used the ophthalmoscope, I examined the eye myself. I examined the right eye first and found that the nasal side of the retina was not diseased. There were no black pigment spots anywhere to be seen on the nasal side. Somewhat disturbed, I examined more carefully the temporal side of the retina and again I was disappointed because there were no black spots there. After a long and tedious search for the black spots, I had to confess to my friend that the patient had recovered from the retinitis pigmentosa and accomplished it unconsciously without practicing relaxation methods. The doctor could not resist looking at me incredulously. I am quite sure he thought I was not telling the truth. The atrophy of the optic nerve had also disappeared and with its disappearance circulation of the nerve was restored. The size and appearance of the nerve were normal. The patient became able to read 20/20 without any trouble. It is very interesting to observe in most cases of retinitis pigmentosa how much damage can be done to the retina, while the vision remains good. Many physicians believe that night blindness cannot be cured. The majority of these cases in my practice have usually recovered and obtained not only normal vision, but they have become able to see better than the average. All patients who were suffering from chronic retinitis pigmentosa had changes in the optic nerve which were very characteristic. In the first place the blood vessels were smaller than in the normal eye and the veins just as small if not smaller than the arteries which emerged from the center of the optic nerve. In most cases the middle coat of the eyeball becomes inflamed and usually much black material is found in the vitreous. There are well marked changes which take place in the crystalline lens. The back part of the lens becomes cloudy and this cloudiness moves forward toward the center of the lens and clouds all parts of it so that the vision is lowered by the opacity of the lens as well as by the more serious changes which occur behind the lens. A patient sixty years of age came to me for treatment. She said that the doctors told her that she had retinitis pigmentosa and that she could not be cured. Within the last few months her doctor had told her that a cataract had formed. Her vision was zero in the right eye, which had cataract. The vision of the left was about one third of the normal and was not improved by glasses. She had a well marked case of retinitis pigmentosa in which the retina of the left eye was apparently covered almost completely by the pigment spots. In some parts of the retina over an area of more than double the diameter of the optic nerve, the retina could not be seen. The patient was very anxious to have me do what I could for her sight. She said that her husband was a business man and had occasion to travel all over the United States, Canada, and Europe. He frequently took her with him, and whenever they came to a large town where some prominent ophthalmologist had his office, she would consult him about her eyes. I found that the back part of the crystalline lens was covered by a faint opacity which was sufficient to lessen her vision. The patient was given a Snellen test card to practice with for the good eye. In twenty-four hours the vision of the right eye had improved from no perception of light to the ability to read some of the large letters of the Snellen test card at five feet. Improvement in the vision of the left eye was manifest. The great improvement in so short a time in the vision of the right eye was unusual. Treatment for retinitis Pigmentosa and cataract The treatment which improved the vision of this patient was palming, swinging, and reading very fine print. This patient gave evidence that retinitis pigmentosa is caused by a strain or an effort to see. The fact that retinitis pigmentosa in the eyes of this patient was so promptly relieved, benefited, or cured was evidence that the disease was caused by strain. The clinical reports of other cases of retinitis pigmentosa confirm the fact that a strain or an effort to see produces retinitis pigmentosa. The efforts which are practiced by the patient can be demonstrated in every case. When the patient makes an effort to improve the vision, it can be demonstrated in every case that the cause of the eye trouble is always due to this effort and the cure of the disease is always obtained by relaxation methods. I have found that among the methods of relaxation which secure the best results are the memory or the imagination of perfect sight. If the memory or the imagination is imperfect, the disease is not completely relieved or benefited. When one letter of the Snellen test card is seen perfectly, it can be remembered or imagined perfectly. There is no procedure which yields better results in the cure of this eye trouble than the memory of part of a letter, which the patient can demonstrate. It is very interesting to observe that in these cases the memory and imagination are capable of bringing about the absorption or the disappearance of organic conditions. This makes it possible for this treatment to accomplish results readily, quickly, when all other treatment is of no avail. For example, a girl fifteen years of age had suffered from retinitis pigmentosa from birth. The disease was rapidly progressing and it did not seem that any relief would be obtained by any form of treatment; the patient was simultaneously suffering from progressive myopia. Relaxation treatment, the correct use of her memory, and imagination improved the progressive myopia and much to the delight of the patient, the retinitis pigmentosa improved at the same time and continued to improve until all traces of the disease were absent and she was permanently cured. It seems to be one of the peculiarities of the disease that it is variable. Oftentimes it gets better for a short time when all of a sudden, overnight perhaps, the disease will return with all its accustomed forms of black pigment spots, atrophy of the optic nerve, diminished circulation, and incipient cataract. Improved circulation in the eyes cures many vision/eye problems/diseases; Relaxation of mind, body, eyes, eye muscles, neck, eye movement/shifting, central fixation improves circulation in the body, brain, eyes. Retinitis pigmentosa has been observed in cases of glaucoma, chronic cases which progressed with more or less rapidity until almost total blindness was observed. In other cases, different parts of the choroid would be destroyed, and there would be loss of vision in these areas. The vision of children ten years of age, suffering from this disease, has been remarkably improved by swinging the child in a circular direction several times daily repeated for many weeks. This promotes relaxation. It is a mistake to dispose of cradles, rocking chairs, and other methods of promoting the swing. The long swing, (described several times in this magazine) is a very efficient method of obtaining relaxation. Many people object that children have not sufficient intelligence to practice the swing successfully. On the contrary children ten years of age or under can practice the long swing as successfully as many adults. It is a treatment that the patient enjoys to a decided extent. Games of all kinds should also be encouraged. It is well to protect the child from adults and others who make the child nervous. Nervousness always causes strain. Laughter and good time are relaxing. The kindergarten is a good place for all children at an early age, because relaxation methods of the best kind are taught there. Before closing, reference should be made to a girl fourteen years of age who cured herself of retinitis pigmentosa by playing games and engaging in sports that she enjoyed. In the summer time she enjoyed swimming and diving from very great heights; in the winter time she practiced skating, devoting long periods of time to this sport. Besides the relaxation methods which I have described, it is worth the trouble to teach children who have so-called incurable diseases how to enjoy themselves for long periods of time both winter and summer. Their eyes as well as their bodies are kept in motion while playing games or engaging in sports which relieve the stare and strain that cause imperfect sight. It is so much more efficient and better than drugs. A LESSON FROM THE GREEKS By W. H. BATES, M.D. The failure of the muscles of the eyes to function normally under the conditions of civilization is not an isolated phenomenon. As Diana Watts, in her remarkable book, The Renaissance of the Greek Ideal (Frederick A. Stokes Company, New York), points out, the entire muscular system of modern civilized peoples works under such a condition of jar and strain that all muscular labor is accomplished with a maximum of effort. So far, indeed, have we drifted from our normal physical possibilities that the positions of the ancient statues seem impossible to us, and we have been forced to attribute many descriptions of the feats of heroes in the Iliad and Odyssey to poetic license. Mrs. Watts, by reproducing the positions of these statues, and doing other things that are beyond the power of even the strongest gymnasts and dancers trained under present methods, has fairly established her claim to have discovered the secret of Greek physical supremacy. Greek athletics, according to Mrs. Watts, was very far from being a matter of mere muscle development. Its aim was to produce a condition in which all the muscles worked harmoniously together and responded instantly to the mind's desire, thus securing a maximum of activity with a minimum expenditure of energy. The secret she found to be very simple. It consists in such a perfect balancing of the body that whether it is at rest or in motion its centre of gravity is always kept exactly over its base. This perfect equilibrium involves in turn a condition of the muscles in which they are transformed from a dead weight to a living force. In this condition there is said to be a complete connection of all the muscles with the center of gravity; independent motions and independent reactions are eliminated, and a combined force is instantly brought to bear upon whatever work is required. The spine is perfectly straight, the waist muscles firm, and the weight, in the standing posture, is supported upon the balls of the feet. Extraordinary precision and beauty of movement results, and all sense of fatigue is said to be abolished. To attain this equilibrium in its perfection requires much study and practice, but it can be approximated simply by keeping the spine straight and the weight over the balls of the feet, or upon the thighs, if seated. By this means a large degree of relaxation is often obtained, and the effect upon the eyesight has, in several cases, been most marked. A patient suffering from retinitis pigmentosa found that when he straightened his spine, in walking or sitting, his field at once became normal, remaining so as long as the erect position was maintained. His field had already improved considerably by other methods, but was still very far from normal. In the evening the position had the further effect of relieving his night blindness. Another patient who had been under treatment for some time for a high degree of myopia without having become able to read the bottom line of the test card, read it for the first time when her body was in the position described. She was able, moreover, to maintain the position for a considerable length of time, whereas ordinarily she was extremely restless, and could not remain still for more than a moment. A third patient, who could not rest her eyes by closing them or by palming, was relieved at once by this means, as was shown, not only by her own feelings, but by the expression of her face. Sleeping with a straight spine has also been found to be a very effective method of improving the vision and relieving fatigue. The patient with retinitis pigmentosa whose case has just been referred to, suffered continual relapses in the morning. No matter how well he saw in the afternoon, or in the evening, he would wake up unable to distinguish the big C and with his memory so impaired that it would take him the whole morning to get it back. After sleeping on his back, with his lower limbs completely extended and his arms lying straight by his sides, he was able to see the fifty line at ten feet when he woke and his memory was much better than usual at that time. Further improvement resulted from further sleeping in this posture. The patient with myopia had been in the habit of waking up tired after ten or twelve hours' sleep. One night she shared her bed with a guest, and in order not to disturb the latter she tried to keep her body straight. Although she had staid up until a very late hour talking, she awoke feeling perfectly refreshed. Another myopic patient who had been at a standstill for six months, gained two lines after sleeping on his back for one night. SAVED FROM BLINDNESS By PATRICIA PALMER It is very hard for an active young girl to suddenly learn that in a short time she may lose her eyesight. I had always felt a great deal of pity for blind people, but I never stopped to realize how many beautiful things they missed until I knew that I was going blind myself. I only wore glasses for three years, but in that short time I developed a very bad case of progressive myopia. In the summer of 1918 my sight became so poor that I had to stop reading altogether and even a moderately bright day hurt my eyes so much that I kept them bandaged a great part of the time. Finally I had to put on a dark Krux lens, and the goggle-like glasses that I wore shut out all light. In the fall I started school, but as I could not see to read I was working under great difficulties. Then, through an article published some months before in the Scientific American, we learned of Dr. Bate's work and it seemed the last possible hope. I declared that there was no use in taking the trip to New York, because I knew he could do nothing for me, but in the end I went. The first time I looked at the test card I could not see the big "C" until I stood within four feet of it, but in two hours I was able to flash all the letters of the third line and part of the fourth at ten feet. In four weeks I had 10/10 vision and my hearing, which had been bad, was normal. Some weeks after I returned home a friend, who was calling, complained of a bad headache. I persuaded him to take off his glasses and showed him how to palm and swing the letters on the chart. A short time later he discovered, to his surprise, that his headache was entirely gone. This incident made me realize that if I showed others what Dr. Bates had shown me I could relieve, if not cure, their troubles. The next person that I worked with was a little girl with progressive myopia which had not become very serious. She worked very conscientiously, and about a month after we started, when she visited Dr. Bates, her sight was nearly perfect. I have helped a number of people, some successfully, others not so successfully. One of my most interesting cases was a chauffeur who thought that he was unusually farsighted, but who could not see to read the paper. When I tested his eyes I found that he had only 10/20 vision. In a short time, however, he attained normal sight by palming and swinging the letters. I then told him to close his eyes and count ten, then open them for a fraction of a second. I held a book in front of him and in a short time, by closing his eyes and then glancing at it, he read parts of it. He practices on signboards, automobile licenses, or anything that he sees, and now he reads the entire paper every evening. He has noticed, too, that he is not blinded by bright lights at night as he used to be. As to the value of swinging the little black period I am very decided. I find it my best friend, especially in a test. One time in a French examination, in the excitement of the moment, I could not think of a certain word which I knew well enough and which was very important to me. I closed my eyes and palmed for a second and remembered the period. In a flash my self-control returned to me and with it the word. I have tried this several times since, usually with success. I often wonder now how I could possibly have managed without my eyes, even with glasses. It is such a joy to be able to read from morning to night if I want to. Reading music is supposed to be a terrible thing for the eyes, but I do an endless amount of it and never know the difference. I find, too, that since my eyes have been well I memorize remarkably quickly, and that when I study I can grasp the contents of the text more easily than before. In the old days of glasses I had to read my history assignment two or three times before I knew what it was about, while now once is quite enough. My greatest regret is that so few people know how to prevent eye troubles, or how to care for them after they develop. Perhaps, however, if the movement to establish Snellen test cards in the schools grows, thousands of children may be saved the agony which I and many others suffered with headaches as well as being freed from the inconvenience of glasses. Ophthalmologist Bates BETTER EYESIGHT MAGAZINE with Translator, Speaker; https://www.cleareyesight.info/naturalvi...atesmethod - FREE Bates Method Natural Vision Improvement Training, 20 Color E-books. YouTube Videos; https://www.youtube.com/user/ClarkClydeN...rid&view=0 - Phone, Google Video Chat, Skype Training; https://cleareyesight-batesmethod.info |

|||

|

« Next Oldest | Next Newest »

|

| Messages In This Thread |

|

Retinitis Pigmentosa - ClarkNight - 07-10-2014 08:12 PM

|

User(s) browsing this thread:

Search

Search Member List

Member List Calendar

Calendar Help

Help